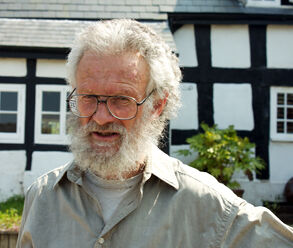

MIAR Arts Welcomes Charles Bound

MIAR Arts welcomes Charles Bound into the gallery.

Charles lives in a farm in Wales and fires his pots in a wood fired tunnel kiln.

Charles talks about his work and the firiing process:-

"When I was offered space on a farm, I built a tunnel kiln and began seriously finding out what was going on and how I might use it. I began to see some of the satisfaction of working with a tool offering much but with its own way of doing so.

Subsequently, the ten years I have been firing in a tunnel kiln have been an ongoing negotiation between what goes into the kiln (what forms, clay, additions, packing arrangements), how the kiln fires, and what I have learned to see in the results to be able to move on, holding at bay as best I can existent prejudices.

In the process, I have increased my capacity to see both what is possible in the kiln and how the results refer back to the environment where we live and work so that muted colours and simplified shapes have become more acceptable and encouraged.

Being on a farm meant materials such as chaff, old bolts and straw got into the clay, and the process of helping occasionally on the farm offered insights on how to do things, solve problems and recognise natural shapes incline to simplicity even when complex. This seeing has come partly just from the ongoing involvement with clay and work but also because a wood fired kiln is an active participant in the results. The kiln offers things I would never have seen or considered had I greater technical expertise and control of the process and outcomes.

So, I have gotten the taste for working with the clay as it presents itself and working into it rather than being primarily concerned with surface. As things come out of the kiln with fused sand from the floor attached, distorted, occasionally with bits spalled off, I have also begun to cultivate the wreckage that occurs in a wood kiln, while at the same time trying to create a stillness in each piece from the complexity of the working and firing, often re-firing, occasionally grit blasting, and assembling or re-firing shards from a waste heap.

The kiln has become a partner, its often seemed cussedness offering glimpses of possibilities by its nature, such as to have different parts of a piece in completely different atmospheres (part open, part buried in embers) or to stress the clay enough to provide cracks as opened lines that complete a pot (particularly large plates fired upright on their rims).

These glimpses, which fall broadly into categories I once assumed failures offer consideration of directions to work in, develop; and occasionally something simple and beautiful comes out of the kiln: a found object, a bit of earth, that suggests to me much of what I've gradually come to recognise I'm investing my energy in. Occasionally a piece arrives that equally refers to being man-made and the materials it came from. And that is always immensely satisfying."